What is the risk of a hard landing in China?

Key points

-

Chinese growth will slow but a hard landing is unlikely.

-

The slowdown in Chinese growth may drive a correction in commodity prices, but sharp falls are not likely. A soft landing in China will be positive for Asian and Australian growth generally.

-

While it’s too early to say for sure that Chinese shares have hit bottom, they are now good value again.

Introduction

With the US flirting with recession, the emerging world, particularly China, is being relied upon to ensure a soft landing for the global economy. Recently there has been reason for concern though. China’s economy is slowing, inflation has surged and its shares are down nearly 50%.

The Chinese economy is slowing

For some time the Chinese authorities have been using a combination of monetary tightening, tax changes, administrative controls and a faster appreciation in the Renminbi to slow and rebalance Chinese economic growth. This has primarily been motivated by a desire to reduce inflation and rebalance growth away from exports and investment towards consumption.

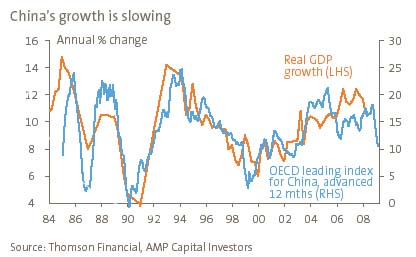

March quarter data showed a slowdown in GDP growth to 10.6% over the year to the March quarter from a peak of 12.4% in the June quarter last year. Loan growth also appears to be slowing. What’s more, the OECD’s leading indicator for China suggests a significant slowdown ahead.

A further slowdown in Chinese growth will take pressure off commodity prices, including oil.

…but don’t expect a hard landing

While China appears to be slowing it’s unlikely to have a hard landing, which given China’s potential growth rate of around 8% to10% and its need to find jobs for roughly 10 million rural workers each year, would mean growth of around 5%.

- Firstly, while the OECD’s leading indicator for China is down, it has understated growth in recent years.

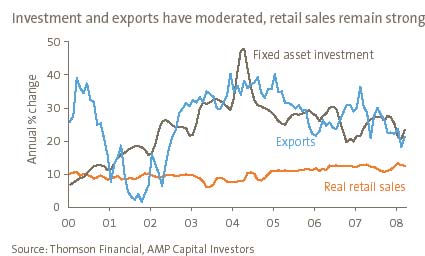

- There is no sign of any consumer slowdown. In fact, the authorities have been trying to boost it via a range of policies including social security reforms, labour reforms and assistance for rural workers. Policies to rebalance growth from exports and investment to consumption seem to be working. See chart below.

-

Much of the slowdown so far in China has been driven by softer growth in exports at a time when imports remain strong. This has been mainly driven by slower growth in exports to the US. It’s worth noting though that China’s exports are hardly collapsing (despite all the talk of rising costs, the rising Renminbi and China’s dependence on the US). China is well placed to handle the US downturn. China’s export growth to the US has been slowing and now amounts to only 18% of total exports whereas exports to Europe (23%), Asia (47%) and other developing markets have been rising. Similarly consumer exports to the US have been declining in importance relative to capital goods. Of course, if the US has a deep and drawn out recession then China will be much more vulnerable. China’s export story is also underpinned by China’s growth in global market share as a low cost producer. This has levelled off in the US but not elsewhere and China is still moving into more value added exports such as machinery where it still has a huge cost advantage.

-

With the 1-year benchmark lending rate at 7.47% and well below nominal GDP growth of 15% plus, China’s monetary environment is still far from tight.

- If growth does fall sharply, China is well placed to ramp up infrastructure spending as in the late 1990s.

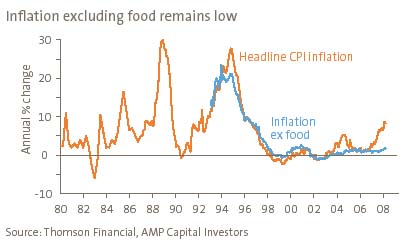

- While inflation in China is high, it’s mainly due to surging food prices which have a 34% weight in China’s CPI (which is double the weight for food in Australia’s CPI). Non-food inflation remains low at just 1.8%.

It’s also worth noting that there is some evidence that China’s energy policies and desire to redistribute growth inland are bearing fruit. Production in China’s energy and resource intensive industries has slowed. Furthermore, while investment in coastal regions has slowed it has accelerated in China’s inland provinces.

So, while it’s likely that China’s growth rate will slow further, a hard landing is unlikely. China is well placed to withstand the US downturn (providing it is not deep and drawn out) and the Chinese authorities are not trying to crunch growth.

But what about collateral damage from shares?

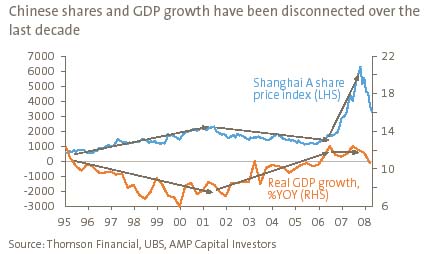

Since peaking last October the Chinese share market has had a fall of nearly 50% on the back of tighter monetary policy, the 20% slump in global shares and worries about the impact of the US downturn. This followed a 132% pa gain over the previous two years, so the 50% fall needs to be seen in context. However, it’s unlikely that there will be a significant impact on the Chinese economy.

-

Over the last decade the Chinese economy and share market have diverged. While shares moved up in the second half of the 1990s the economy slowed, and the reverse occurred from 2001 to 2005. Through 2006 and 2007 shares surged but growth ranged sideways. See the next chart.

Inflation is nowhere near the 25% plus of the late 1980s and mid 1990s and this partly reflects the surge in capacity enhancing investment in recent years. So while the authorities want to slow growth down to ensure inflation doesn’t become a generalised problem beyond food, they don’t want to crunch growth because it will just expose excess capacity and deflation.

-

Concerns that the aftermath of the Beijing Olympics will see growth slump are misplaced. Beijing has just over 1% of China’s total population and just less than 3% of its GDP. These are likely the lowest ever for an Olympic city. The comparable figures for Sydney are around 20/25%. So a post Olympic slump in Beijing will have little impact on the whole Chinese economy.

-

Finally, structural forces driving growth remain very strong. These include strong productivity growth, huge competitive advantages, rapid urbanisation, surging consumer demand and very strong investment. With per capita income levels in China still way below rich country levels China’s rapid growth phase has a long way to go, probably several decades.

While it’s too early to say for sure that the Chinese share market has hit bottom, the recent slump restored value to Chinese shares, with the price to earnings multiple falling from over 50 times back to 24 times which is below its long term average and is reasonable given profit growth is running around 30-40%. Recent Government moves to ease the sale of non-tradeable shares and cut stamp duty on shares provide support for the market and suggest the Government thinks it has fallen enough.

Concluding comments

China’s economy is likely to slow over the year ahead in response to slower exports and domestic tightening. However, a hard landing is unlikely and we see growth slowing to around 9.5% which will still leave it as the world’s strongest growing major economy. This will help ensure that commodity prices remain reasonably strong, notwithstanding the potential for a decent correction as Chinese growth slows, and will help ensure the Australian economy is not dragged down with the US. Chinese shares are now good value again on a longer term basis.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors